Arch History

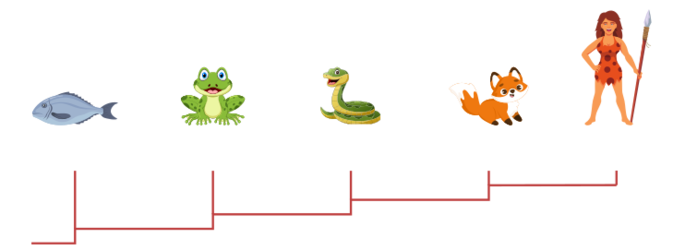

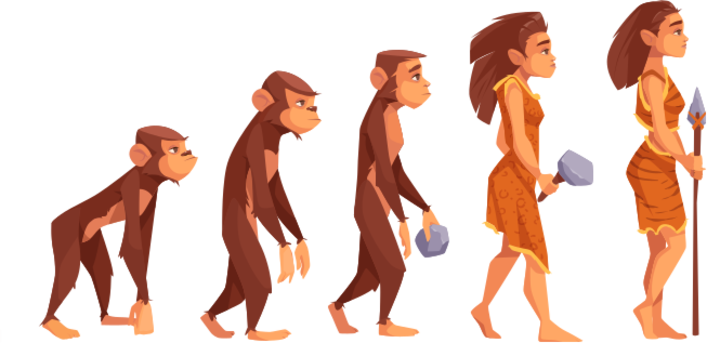

This expansive narrative explores the grand sweep of cosmic and human history, charting the course from the universe's inception to the complexities of contemporary civilization and beyond. It starts with the cosmic cycle and stellar genesis, detailing the processes that forged chemical elements and sparked life on Earth. The journey progresses from the simplicity of early cellular life to the intricate networks within ecosystems, illustrating the evolution of life across epochs, and culminating in the emergence of human consciousness and society.

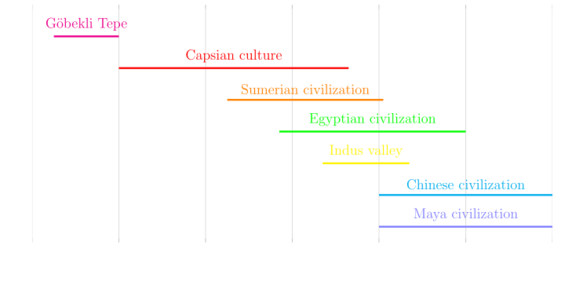

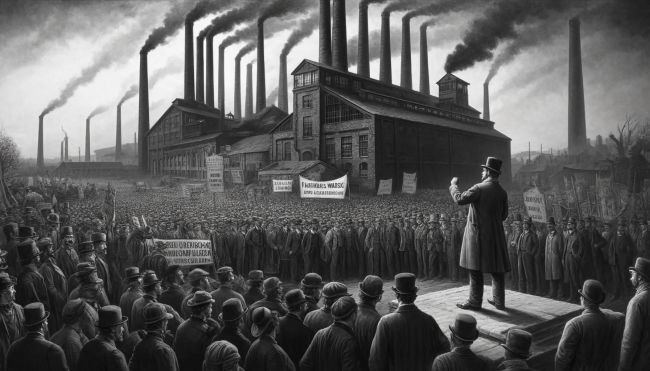

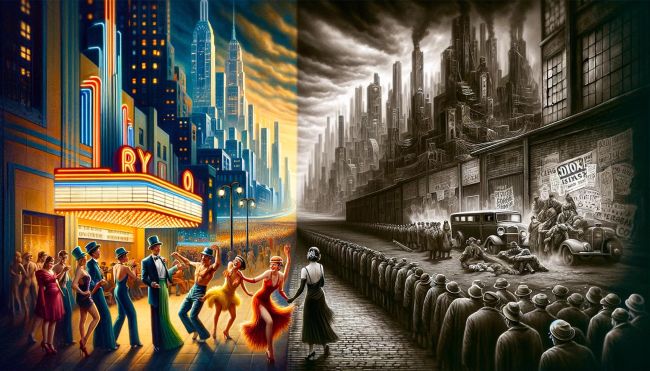

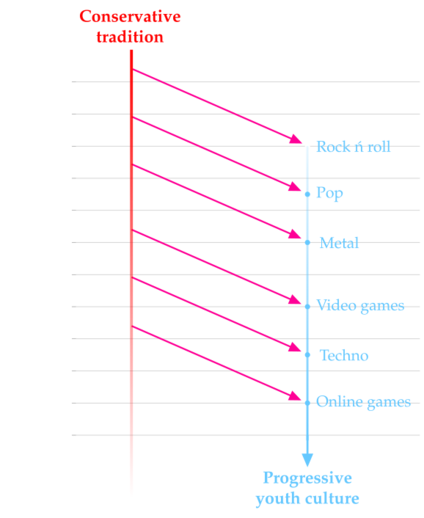

As the focus shifts to the development of human societies, we explore cultural innovations and the rise of civilizations worldwide, addressing significant periods like the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and the Enlightenment. This account also navigates through the technological surges of the Industrial Age, the upheavals of the Second World War, and the transformative impacts of global institutions and the digital revolution in the modern era.

The narrative culminates in a profound examination of the scales of reality, from the minutiae of quantum mechanics to the expansive cosmic vistas, prompting a reevaluation of our place within the universe. This article is more than a chronological recount; it is an exploration of the deep interconnectedness between life, society, and the cosmos. By broadening our historical perspective to encompass the entire timeline of the universe, we invite readers to forge a new and expansive identity—seeing themselves not just as citizens of a nation, but as integral parts of a larger cosmic story, linked by shared heritage and common destiny across time and space.

From Cosmogenesis to Primates

The Cosmic Cycle

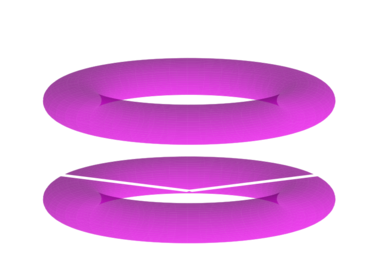

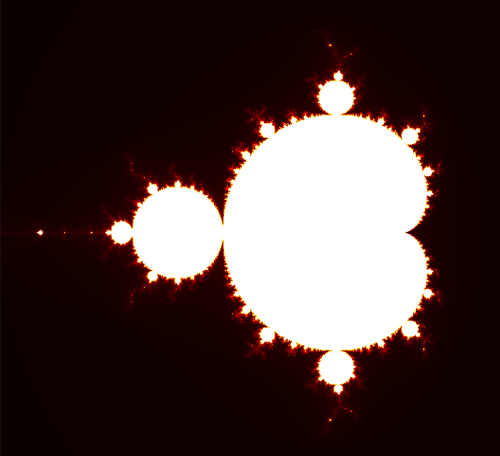

In Sir Roger Penrose's Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC), the universe's history is perceived not as a linear sequence with a singular beginning and end but as a continuum of epochs known as 'aeons.' Each aeon begins with a Big Bang-like event and concludes in a state resembling heat death, where the universe cools and expands to such an extent that conventional matter ceases to exist, and traditional measures of time and scale lose their significance.

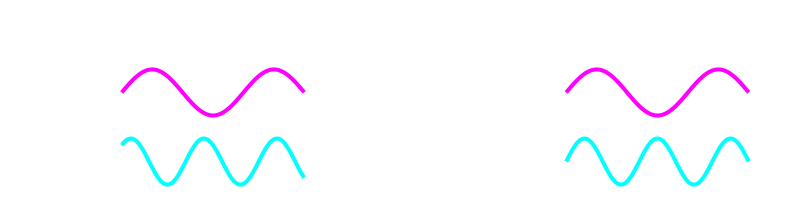

Within this framework, the principles of scale invariance take on heightened importance. Maxwell’s equations in a vacuum and Dirac’s equation for massless particles, for example, demonstrate an intrinsic symmetry of nature that remains constant regardless of scale. These equations, governing electromagnetic fields and the behavior of particles like neutrinos, suggest an underlying uniformity across various scales, hinting at a universe where fundamental laws persist unchanged through transformations of scale. This universal behavior, transcending mass and distance, points to a deeper unity within the cosmos, suggesting that the fundamental nature of the universe may exhibit a timeless uniformity.

This concept of scale invariance becomes particularly significant in a universe dominated by photons and massless particles, as postulated in the latter stages of each CCC aeon. In such a universe, entities without intrinsic size or scale suggest that discussions about 'size' are only meaningful in relation to other objects. A universe composed solely of such particles would inherently embody scale invariance, lacking a definitive size due to the absence of mass to provide a scale through gravitational interactions. It could be described as infinitely large or infinitesimally small, with such descriptions being functionally equivalent. This dimensional ambiguity implies a universe where traditional metrics of size and distance become irrelevant.

Penrose further postulates that during the transitional phase between aeons, the universe's remaining massless constituents, such as photons, exist in a state that might be regarded as timeless and scale-invariant. This phase, where conventional spacetime constructs dissolve, echoes the concept of the divine oneness found in various spiritual and philosophical traditions, illustrating a profound conceptual resemblance that bridges scientific and metaphysical viewpoints.

This divine oneness represents an undifferentiated, nondelimited reality, an absolute unity that transcends the known physical laws, dimensions, and limitations. It is the pure potential from which all forms manifest, akin to the undisturbed singularity from which the universe periodically springs forth according to CCC. Here, the uniform, coherent state between aeons mirrors the spiritual concept of oneness, where all distinctions merge into a singular state of existence.

The birth of the physical universe, or cosmogenesis, can be envisioned as emerging from a state of divine oneness, characterized by scale-invariant massless particles. This primordial phase, much like the process of decoherence in quantum physics, marks the universe's transition from a superposed, quantum state into a classical state where distinct outcomes and entities become defined. In this cosmic-scale decoherence, the universe shifts from being dominated by scale-invariant, massless particles that exhibit no distinct sizes or scales, to a state where scale-dependent, massive particles emerge, bringing with them the varied scales and structures characteristic of the physical cosmos.

Just as decoherence in a quantum system leads to the collapse of superpositions into observable reality, the passage from the oneness of the inter-aeonic phase to the differentiated cosmos of a new aeon can be viewed as a transformation where fundamental properties such as mass, time, and space become meaningful. This transition not only marks the genesis of diversity in forms and structures but also the emergence of the physical laws that govern their interactions, moving from a uniform, homogenous state to one rich with complexity and variability.

This moment of symmetry-breaking heralds the onset of complexity, diversity, and the relentless march of time. Time, as a measure of change and progression from potentiality to actuality, and entropy, as a measure of disorder or the number of ways a system can be arranged, begin to define the evolving universe. These concepts are absent in the initial state of oneness, where change and disorder are not applicable.

The end of time can be conceptualized as a process of 'recoherence,' where the universe, after navigating through all stages of evolution and entropy, transitions back to a state of fundamental unity. This theoretical recoherence might involve achieving a scale-invariant state, where all physical distinctions and conventional measures of scale dissolve. As the universe cools to approach absolute zero, phenomena akin to Cooper pairing and decay into bosons could facilitate this transition. As time approaches infinity, the maximum information density of the universe may approach zero, potentially prompting a collapse back to massless, scale-invariant particles. This reduction in complexity could lead to a state similar to a Bose-Einstein condensate, where particles occupy the lowest quantum state, enabling a macroscopic quantum phenomenon in a uniform, indistinguishable field. In this ultimate phase, the universe could revert to a primordial condition that transcends the familiar constraints of space and time, erasing the distinctions that currently define the cosmos and echoing a return to its earliest, simplest state.

In Einstein's theory of relativity, as objects move closer to the speed of light, they experience a contraction of space and a dilation of time from the perspective of an external observer. This effect, known as Lorentz contraction, is most extreme near black holes, where the gravitational pull is so intense that not even light can escape. Light, perpetually traveling at its intrinsic speed, represents a constant bridge between timelessness (as it experiences no time due to its speed) and temporality (as it marks the flow of time in the universe). In this sense, light acts as a transactional element, constantly interacting with the fabric of spacetime and influencing the transition between states of being.

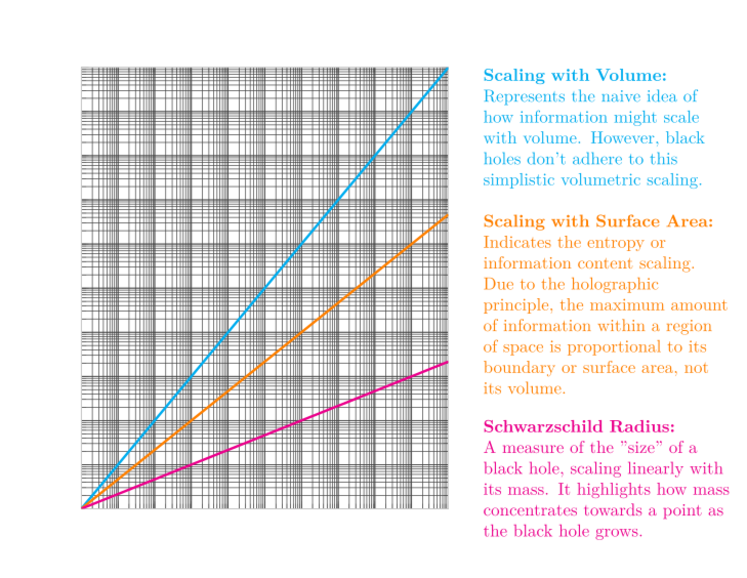

Black holes, meanwhile, epitomize the extremity of spacetime curvature, creating conditions where the usual laws of physics encounter their limits. At the event horizon of a black hole, time for an external observer seems to stop—a literal edge between the temporal and the timeless. Here, light and matter teeter on the brink of entering a realm where time as we understand it ceases to exist. This boundary condition can be seen as a dynamic interaction or transaction, where entities shift from the temporal universe we inhabit to the profound timelessness at the event horizons of black holes.

This conceptualization frames black holes not just as astrophysical phenomena, but as profound transitional zones between the measurable, temporal universe and a state that might be akin to the recoherence at the end of time, linking back to the concept where the universe's distinctions dissolve into a unified existence beyond time. This provides a philosophical and scientific scaffold to ponder deeper into the mysteries of cosmic existence and the ultimate fate of all universal constituents.

The Role of The Divine Oneness

Consider the unfolding of the universe as a grand narrative, authored by the divine oneness. In this vast cosmic story, the divine oneness meticulously crafts the main outline, setting the stage for the overarching direction and purpose of the universe. This process of outlining is one and the same with the manifestation of the universe’s foundational laws, initial conditions, and significant evolutionary milestones. However, this grand narrative, inherently dynamic, allows for the emergence of subplots and minor narratives. Governed by smaller systems—such as individual beings, communities, and natural processes—these sub-narratives unfold within the divine framework, embodying a degree of autonomy. These smaller narratives, while mostly harmonious with the main outline, sometimes diverge from the intended plot. Within these deviations, some systems, driven by free will, ignorance, or other factors, engage in actions that can be described as 'evil' or harmful. Such actions represent a misalignment with the divine oneness's overarching plan, introducing conflict, suffering, and chaos into the world.

The existence of these divergences is not an oversight but a feature of a universe designed with free will and the potential for growth, learning, and redemption. The divine oneness, in its infinite wisdom, allows for these smaller systems to exercise free agency, knowing that through their choices, beings have the opportunity to align more closely with the main outline over time or to learn from the consequences of misalignment.

In essence, the divine oneness sets the universal principles and goals, akin to a master storyteller outlining a narrative. The smaller systems—individuals and collectives—then contribute to this narrative, weaving their own stories within the broader tapestry. It is precisely this dynamic interplay between the divine plan and the free actions of smaller systems that reveals the full complexity and beauty of the universe, with all its challenges and opportunities for reconciliation and alignment with the divine will. This interplay is made possible by the divine oneness's act of embedding freedom into the very fabric of existence, a testament to its intention to create a cosmos that is vibrant and alive, rather than a static, deterministic machine. Such freedom is the catalyst allowing systems to operate with autonomy, fostering a universe where creativity, diversity, and the potential for unforeseen possibilities can flourish. It's a deliberate design aimed at making the universe a dynamic and interactive canvas of existence.

In the realm of quantum mechanics, the principle of freedom finds a parallel in Born's rule, which describes how the probabilities of the outcomes of quantum events are determined. This rule illustrates that even at the most fundamental level, the universe does not strictly adhere to a predetermined path but is influenced by probabilistic behaviors, allowing for a spectrum of possibilities. This inherent uncertainty at the quantum level is a reflection of the freedom imbued by the divine oneness, manifesting in ways that defy classical deterministic explanations.

For cognitive systems, such as humans, this freedom is experienced subjectively as free will. It's the sensation that we can make choices that are not entirely preordained by our past experiences or the initial conditions of the universe. This sense of free will is crucial for the development of consciousness, morality, and personal identity. It allows cognitive beings to navigate their existence, make ethical decisions, and forge their paths through the myriad possibilities that life offers.

This divine gift of freedom ensures that the universe and its denizens are not mere cogs in a cosmic machine but active participants in a continuously unfolding story. It's a testament to the divine oneness's desire for a universe replete with life, growth, and the capacity for transformation. By endowing the universe with this freedom, the divine oneness invites all of existence to partake in an ongoing dialogue between the potential and the actual, between what is and what could be.

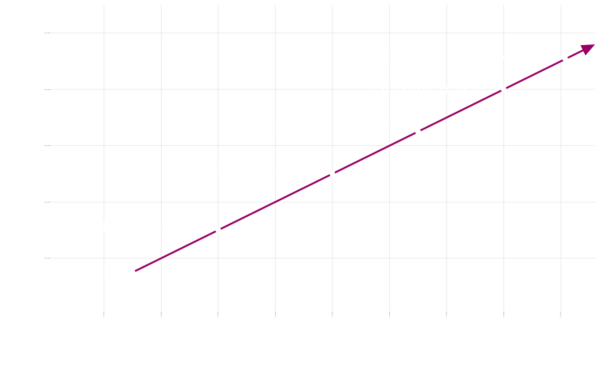

The Arrow of Time

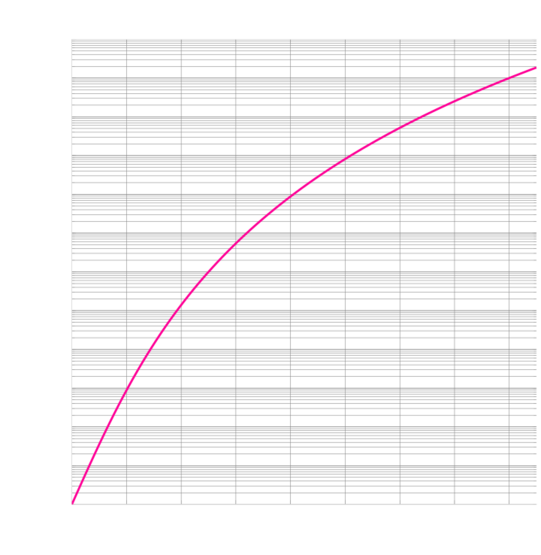

The narrative of our universe unfolds from a seminal moment of extraordinary density and low entropy, a boundary phase that prefaced its metamorphosis into the expansive cosmic theatre we observe today, some 13.8 billion years later. It is a narrative marked not only by the universe's relentless expansion but also by the concurrent ascent of entropy. Yet, in this grand progression, a compelling paradox emerges: amidst the rise of disorder suggested by increasing entropy, there exists a counterpoint—the diversity of forms and the intricacy of structures have also been ascending. With time, we witness the emergence of ever more complex systems, from the first atoms to the elaborate tapestry of galaxies, stars, planets, and the intricate dance of life itself. This dual evolution underscores a profound cosmic dichotomy: as the universe ages and disorder grows, so too does the potential for complexity and the richness of differentiated forms, contributing to the vast mosaic of existence.

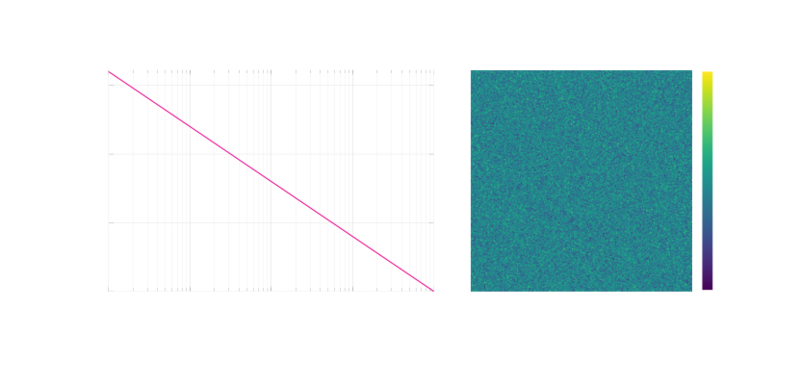

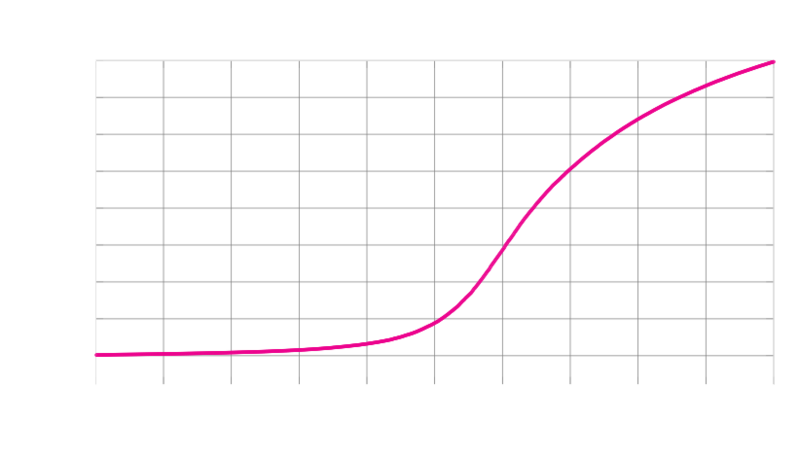

Nearly Scale-Invarient Gaussian Noise in the Cosmos

The cosmic microwave background (CMB) provides a detailed snapshot of the cosmos as it stood during its early stages, a period known as cosmogenesis. One of the key characteristics uncovered in the CMB is the subtle non-uniformity across different scales, manifested as temperature and density fluctuations. These fluctuations exhibit a pattern that is nearly scale-invariant, indicating that there is a slight preference for larger fluctuations at larger scales, identifiable by a gentle tilt of approximately 4% in their amplitude. This trend in the Gaussian noise of the CMB is a fundamental aspect of the universe’s early structure and has been extensively studied to understand better the statistical properties of these fluctuations. The Gaussian aspect of the fluctuations refers to their random, yet statistically predictable nature, with a distribution of temperatures that follows a Gaussian, or normal, distribution curve.

The nearly scale-invariant spectrum, with its small deviation, suggests that the early universe's fluctuations had a specific distribution where the size of the fluctuations became marginally more significant as the scale increased. This 4% tilt indicates a delicate excess of power on larger scales—a feature that has been the subject of intense study to decipher the early universe's physical processes. Recent theoretical developments suggest that these primordial fluctuations can be calculated directly from Standard Model couplings, without invoking inflation. This approach not only grounds the observed properties of the CMB in known physics but also aligns with the preservation of CPT symmetry, indicating a potentially mirrored symmetry in the early universe that is observable in the CMB’s uniform temperature distributions.

Furthermore, insights from Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC) introduce the possibility that the observed patterns might carry imprints not just from the early stages of our universe but from the cyclic transitions between aeons. This perspective offers a broader, possibly infinite context to the dynamics that governed the cosmos's thermal and density characteristics at a time close to its genesis. Understanding the near scale-invariance of these fluctuations and their slight tilt is key to piecing together the universe's history from its earliest epochs to the present day, potentially revealing a cyclic nature of cosmological evolution.

The Entropic Force

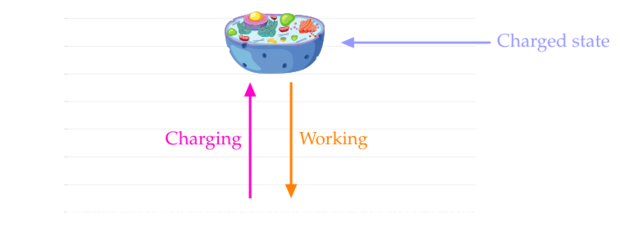

Picture the universe as an immense power cell. The emergence from the vector boundary signifies the initial charging phase of this cosmic battery, infusing it with an extraordinary quantity of energy and potential. This was manifested in the form of matter, antimatter, dark energy, and quantum fluctuations. As time rolled on, this stored energy was gradually depleted, much like a battery, through various processes like the birth and evolution of galaxies, the creation of stars and planets, and the emergence of life. Similar to a battery converting stored energy into useful work, the initial energy of the universe has been the driving force behind all the natural processes and transformations we witness today.

Imagine the early universe as a colossal boulder, perched on the highest point of a steep hill, symbolizing a freshly charged cosmic battery at the moment just after cosmogenesis, saturated with a seemingly limitless store of energy and potential. This monumental event breathed life into the universe, begetting galaxies, stars, and planets in a dynamic ballet of cosmic evolution. Each period in the cosmic timeline might be seen as different segments of the boulder’s pathway down the hill, depicting the universe’s gradual but relentless expenditure of energy as it fosters new phenomena, structures, and elements in its descent.

Fast forward billions of years to our current chapter in this grand tale. The boulder, though having covered vast distances, maintains the momentum gifted from its inception, perpetually fueled by the dwindling yet potent reserves of its initial energy store. This energy now facilitates the vibrant dance of life, the phenomena we witness on our planet, and the celestial events that occur in the far reaches of the cosmos. We find ourselves in a universe that has journeyed from a concentrated epicenter of potential to a rich tapestry bursting with life, diversity, and splendor, a universe still narrating its ever-evolving story through the intricate ballet of cosmic phenomena.

Exploring the universe through the lens of a fuel source provides another intriguing viewpoint. The original elements of the universe, namely energy, matter, and space-time, can be likened to a slow-burning fuel source, progressively converted over billions of years to power the evolution of the cosmos. This transformation process, governed by the immutable laws of physics, has been instrumental in structuring the universe and steering its expansion. This concept mirrors the principle of energy conservation, according to which energy is neither created nor destroyed, but simply transmuted.

The two metaphors employed effectively emphasize that the foundational conditions of the cosmos, brought to life by emergence from the vector boundary, held the seeds for everything we currently witness in the vast expanse of the universe. They further underline the pivotal importance of energy conversion mechanisms in the unfolding saga of the universe's development, whether we visualize these processes as the depletion of a battery or the combustion of a universal fuel source.

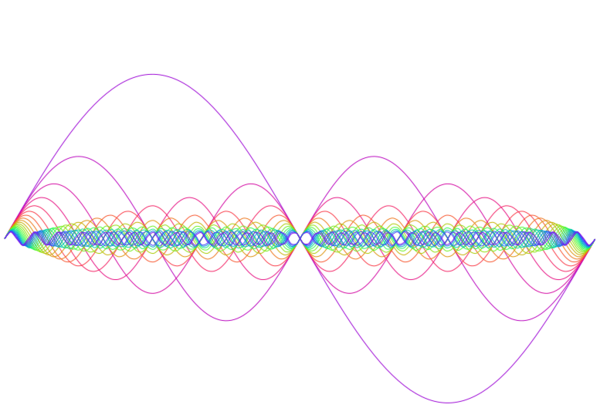

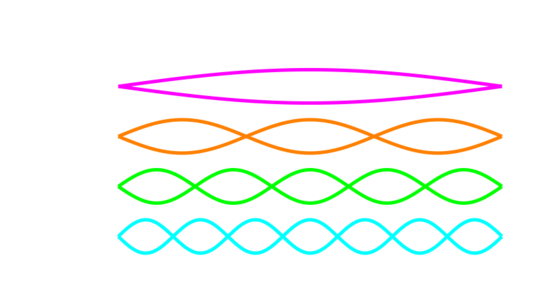

The Consolidating Force

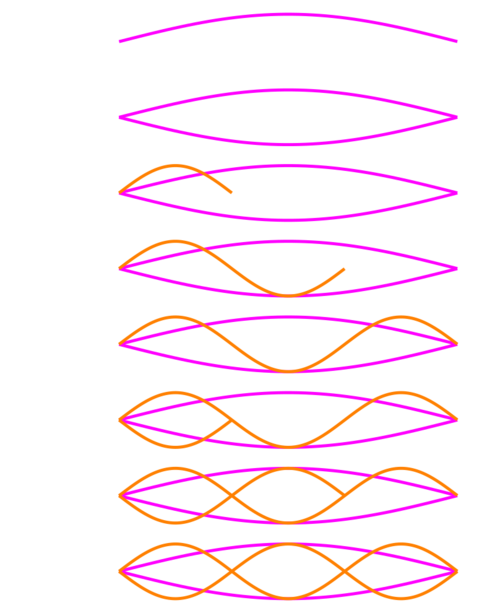

Harmony is a fundamental property of wave interactions in all kinds of systems, not just in music. They are present in any context where waves are produced and can be observed in mechanical waves (like those on a string or in the air, which we hear as sound), electromagnetic waves (such as light), and even quantum wavefunctions of particles. In any of these systems, the harmonic frequencies are whole number multiples of the fundamental frequency—the lowest frequency at which the system naturally resonates. The presence of harmonics contributes to the complexity and richness of phenomena in various fields of science and engineering, from acoustics to electronics, and from optics to quantum mechanics.

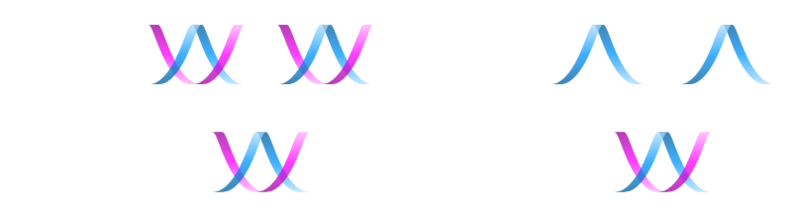

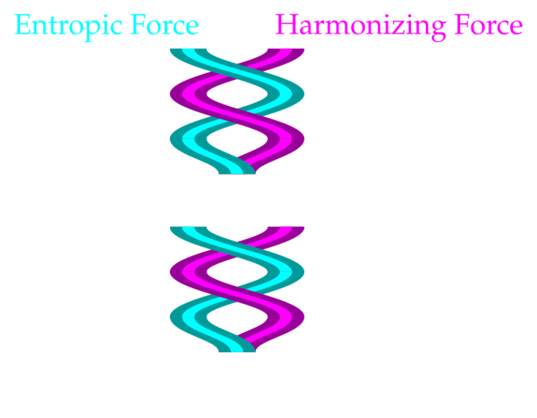

As an entropic force propels systems toward a state of increased entropy, signifying an inexorable drift towards disorder, we may also envision a consolidating force that impels the assembly of larger, more harmonious wholes. This force embodies a fundamental tendency within the cosmos for components to coalesce into a harmonious state, orchestrating a symphony of balance and coherence. It reflects the universe's innate propensity for organizing disparate elements into grand, complex structures that not only exhibit beauty but also represent larger, cohesive aggregates.

The harmonic series in music that illustrates the beauty of individual frequencies coming together in a symphony of complexity. This notion posits that there exists an underlying force or principle that drives the unification of smaller systems into larger, more complex wholes across various scales of reality, akin to the way a fundamental tone harmoniously integrates its overtones into a richer, more profound sound. This force is not merely a mechanical or impersonal process, but one that carries with it an essence of attraction, desire, and creative engagement. Just as individual notes in a harmonic series resonate with one another to create a musical whole greater than the sum of its parts, so too does this cosmic force catalyze the unity and complexity of the universe's vast symphony.

At the atomic and molecular levels, the consolidating force can be seen in the way atoms bond to form molecules. The noble gases are paragons of atomic stability, each boasting a perfectly balanced and harmonious valence shell. This electronic serenity is the envy of the periodic table, where other elements are left striving for such completeness in their outer orbits. These elements embark on a quest for electronic equilibrium, finding solace and stability through the graceful dance of electron exchange, giving rise to ionic bonds, or the intimate waltz of electron sharing, resulting in covalent bonds. Through these interactions, atoms achieve their own state of harmony, echoing the grand symphony of chemical bonding.

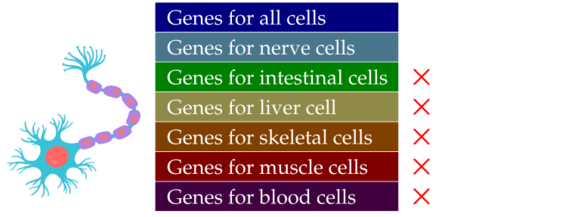

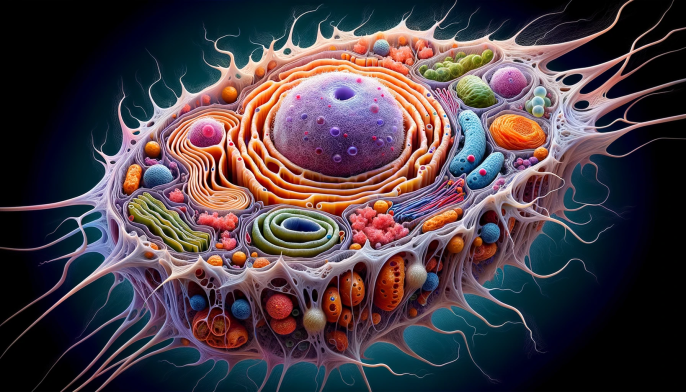

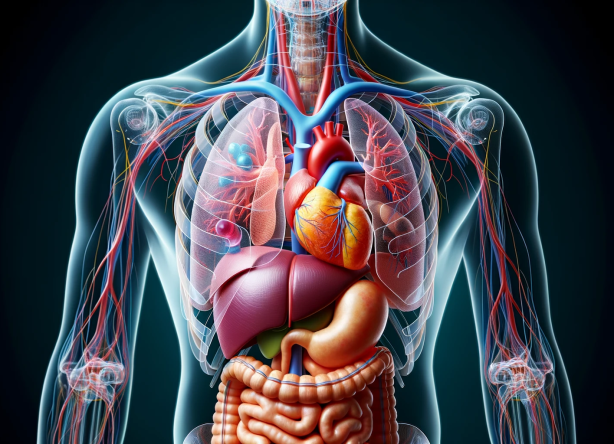

Moving up the scale, in biological systems, the consolidating force manifests in the organization of cells into organisms. Each cell, with its unique functions and potential, collaborates with countless others to form complex living beings. This synergy is not merely functional but speaks to a deeper, intimate interdependence and cooperation that is central to the emergence and evolution of life. It reflects a universal pattern of connectivity and unity, where diverse components integrate to form entities of increased complexity and capability.

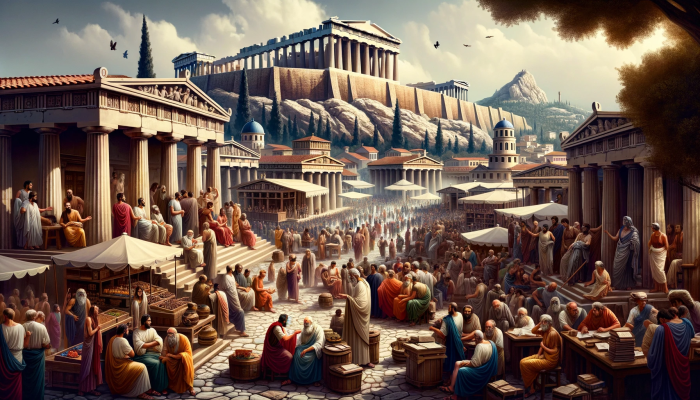

In the realm of human societies, the consolidating force reveals itself in the ways individuals come together to form communities, societies, and civilizations. Here, the force operates through shared ideas, emotions, and purposes, driving the creation of social structures, cultures, and systems of meaning that transcend individual existence. This social cohesion and collective endeavor mirror the harmonizing essence by showcasing humanity's intrinsic drive towards unity, cooperation, and the creation of shared realities that enrich and expand the human experience.

The consolidating force, therefore, represents a fundamental principle of the universe, a kind of cosmic glue that binds the fabric of reality across different scales and domains. It suggests that the universe, in all its diversity and complexity, is underpinned by a force that favors unity, complexity, and the emergent properties that arise when disparate parts come together in harmony. This perspective offers a holistic and integrative view of reality, one that transcends purely physical explanations and invites us to consider the deeper, more mysterious dimensions of existence that drive the evolution of the cosmos towards ever-greater degrees of complexity and connection.

The Buttons-and-Threads Metaphor

The metaphor of buttons and threads offers a vivid and accessible way to grasp the concepts of connectivity and complexity in various systems. Imagine each button as an individual element within a network. This could be a person within a social circle, a neuron in the brain, or a digital node in a computer network. The threads represent the connections between these elements, gradually weaving together to form a more intricate and dense network. As these connections grow, the network evolves into a "giant component" – a strong and interconnected structure that showcases the network's enhanced structure and functionality.

This growth of connections, pulling previously isolated elements into a complex and unified whole, illustrates the principle of the consolidating force – a concept suggesting that there's a natural tendency towards increasing complexity and unity in the universe. This metaphor beautifully captures how individual entities can transcend their isolation to form a cohesive and interconnected collective. It reflects the universe's inherent drive towards complexity and unity, evident at every level of existence.

By using this metaphor, we can better understand how isolated entities within a network can become a complex, interconnected system, whether we're talking about human societies, the neural networks of the mind, or ecosystems. It provides a concrete image of the transition from individuality to collectivity, aligning with the consolidating force's emphasis on unity and the intricate beauty that emerges from complex relationships. In doing so, the buttons-and-threads metaphor not only makes the complexity of networked systems more comprehensible but also celebrates the complexity, highlighting the fundamental patterns that fuel the evolution of order and complexity across the universe.

Teleological Perspectives and the Consolidating Force

The idea of the consolidating force seamlessly aligns with teleological perspectives, which consider the purpose and directionality in the natural world. Teleology, from the Greek 'telos' meaning 'end' or 'purpose,' examines the inherent intentionality or end-goals within natural processes. The consolidating force may be interpreted as a teleological principle, guiding the progression of the cosmos toward higher degrees of complexity and connectivity, much like an artist driven by a vision of the masterpiece they aim to create.

In every layer of reality, from the atomic dance that forms molecules to the grand ballet of societal evolution, the consolidating force can be envisioned as a teleological agent. It is as if the universe is not just a random assembly of atoms but a stage set for a purposeful drama that unfolds according to a cosmic story. This force implies that there is an innate directionality to the cosmos, one that inclines toward a state of complex interrelations and unified wholes.

This teleological view challenges reductionist approaches that see the universe as devoid of intrinsic purposes, suggesting instead that there is a sort of cosmic intentionality at work. While the consolidating force operates within the physical laws of the universe, its manifestations hint at a deeper narrative – one that suggests the cosmos is not just a machine ticking away but a dynamic, evolving entity moving toward a state of holistic integration.

Such a perspective invites us to reframe our understanding of natural phenomena, seeing them not as mere happenstance but as part of a grander scheme of cosmic evolution. It raises profound questions about the nature of life, consciousness, and the universe itself. How do we, as conscious beings, fit into this picture? The consolidating force, viewed through the lens of teleology, offers a rich and fertile ground for philosophical inquiry, one that bridges the gap between science and deeper existential contemplation.

In the vast expanse of our existence, where every being is a unique embodiment of the universe's grand narrative, the consolidating force manifests as a subtle yet profound call to unity. The consolidating force is seen not only in the physical act of connection—person to person, hand to hand—but also in the shared purpose that moves each individual to become a link in this living bridge. It's a metaphor for the universal bond that draws disparate entities together, creating something greater than themselves—a path across the void, a bridge between worlds. Through this cosmic force, the universe reveals its inherent desire for coherence and deeper connection, echoing through the hearts that beat in unison with the rhythm of existence.

Primordial Nucleosynthesis

In the nascent cosmic dawn, from the swirling photon sea, the first whispers of quarks and gluons began to stir, heralding the universe's dramatic unfurling. It was the consolidating force, the universe's intrinsic yearning for complexity and connection, that guided this transformation. As this force worked its subtle alchemy, the abstract, scale-invariant sea of photons coalesced into the tangible fabric of spacetime. This pivotal moment, when the universe assumed its three-dimensional grandeur, also gave birth to our familiar constructs of time and space.

With the universe's relentless expansion and cooling, quarks and gluons embraced under the consolidating force's gentle impetus, giving rise to a period celebrated as primordial nucleosynthesis. In this era of cosmic creativity, they bonded to forge the earliest protons and neutrons, the harbingers of matter as we know it. These nascent particles, driven by the same force that sparked their creation, united to conceive the universe's first atomic nuclei, including the likes of helium-4, deuterium, and lithium-7. Following the first 380,000 years, the universe had cooled to a whisper of its initial fervor, allowing electrons to join with these nuclei, crafting the first neutral atoms and molecules in a testament to the consolidating force's enduring pursuit of unity.

This primordial nucleosynthesis was more than a cosmic event; it was the consolidating force's canvas, upon which it painted the pathways for massive hydrogen clouds. Over millennia, these clouds, drawn together by gravity—a physical manifestation of the consolidating force—began to coalesce. This gravitational dance was the prelude to the cosmic ballet that would see the birth of the universe's first stars and galaxies, celestial bodies that continue to tell the tale of the universe's ceaseless journey towards complexity and the interconnected tapestry of existence.

The Dawn of Stars and Galaxies

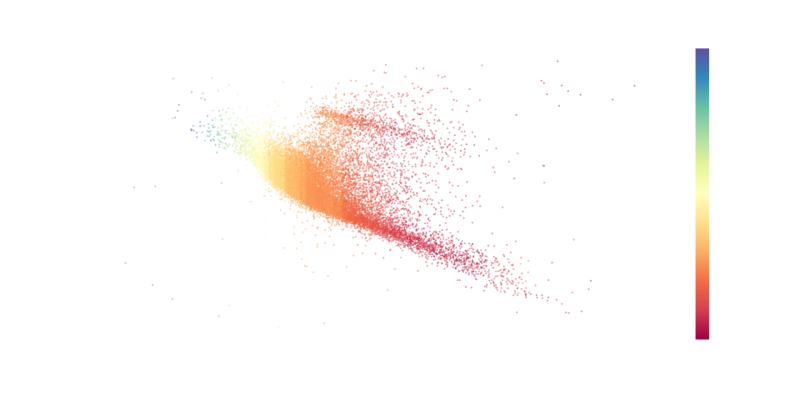

The dawn of the first stars and galaxies stands as a monumental chapter in the unfolding narrative of the cosmos, a time when the universe was a vast expanse of hot, diffuse gas, humming with potential. Within this primordial soup, small density variations—mere echoes of the quantum fluctuations from the universe's infancy—laid the groundwork under the guidance of the consolidating force, the universe's inherent push towards complexity and unity. This subtle but powerful force, the cosmic whisper behind all attraction and connection, encouraged the gas to cool and coalesce, its gravitational embrace preordaining the eventual collapse into the dense cradles of future stars and galaxies.

This consolidating force, a constant throughout the cosmos, orchestrated the gas's journey as it transformed under gravity's pull, converging into nascent celestial bodies. The first galaxies emerged from these cosmic gatherings, each a testament to the universe's propensity for creation and organization.

The genesis of stars within these galaxies unfolds as a testament to the consolidating force's role in cosmic evolution. Nebulous clouds, the nurseries of stars, gradually succumbed to their own gravity, contracting and heating up. The consolidating force acted as a catalyst in this celestial alchemy, fostering the conditions necessary for nuclear reactions to ignite within the dense cores of these clouds. As these reactions flourished, they sparked the transmutation of simple gases and dust into the brilliant tapestry of stars that now light up the cosmos, each star a beacon of the universe's enduring desire for complexity and connection.

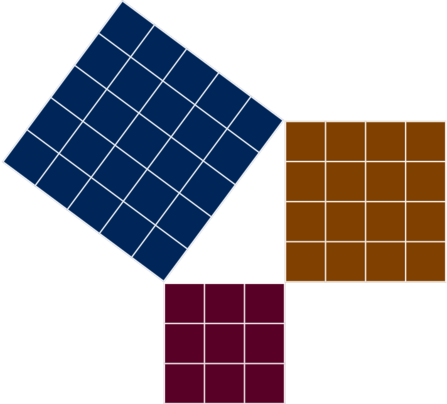

The Hertzsprung-Russell diagram is a pivotal tool in the field of astronomy, serving as a graphical representation that depicts the relationship between stars’ true brightness (luminosity), surface temperature (color), and spectral class. Essentially, this chart acts as a cosmic map, charting the life cycle of stars from birth to their eventual demise. In such a diagram, one axis typically portrays the luminosity of stars compared to the Sun—ranging from less luminous dwarfs to the exceedingly bright supergiants. The other axis is allocated for the stars’ surface temperature or color index (B-V), which inversely correlates to temperature; cooler stars appear red and sit on the right side of the diagram, while hotter stars emit blue light and are found on the left.

The main sequence, the prominent diagonal band stretching from the top left to the bottom right, is where most stars, including the Sun, reside for the majority of their lifespans. Stars in this region fuse hydrogen into helium within their cores. The diagram also features other distinct groupings of stars, such as red giants and white dwarfs, each indicative of different evolutionary phases. Red giants, for instance, represent a late stage in stellar evolution when a star has consumed its core's hydrogen and has begun to expand. A Hertzsprung-Russell diagram is more than just a static portrait; it narrates the dynamic story of stellar evolution. By analyzing where a star falls on the chart, astronomers can infer critical information about its age, mass, temperature, composition, and the stage of its lifecycle. This serves not only to enhance our understanding of individual stars but also to shed light on the broader mechanisms governing galactic evolution.

Transitioning our focus slightly, we can consider the broader physics concepts that help us understand these processes. A key area of study is non-equilibrium thermodynamics, which illuminates the existence of what are known as 'dissipative structures'. These structures – tornadoes and whirlpools, for instance – represent spontaneous formations of order. Dissipative structures emerge as efficient means to dissipate energy gradients within open systems. In such systems, energy consistently flows in from the environment and entropy is generated as the system strives to eliminate the gradient and discharge energy as efficiently as possible. This reveals a fascinating aspect of our universe: entropy and order can coexist within open systems. Indeed, even as a system increases its entropy or disorder, it can also develop complex structures or order, given enough energy flow.

Stellar Nucleosynthesis and Metallicity

Stars, in their celestial crucibles, are the artisans of the cosmos, guided by the consolidating force, the universal pull towards complexity and fusion. Through the process of stellar nucleosynthesis, they wield the power to transmute simple hydrogen atoms into more complex helium, embodying the harmonizing desire for transformation and unity at a cosmic scale. As stars age and exhaust their hydrogen fuel, this same force spurs them on to create increasingly heavier elements in their fiery hearts, a testament to the universe's drive towards greater diversity and intricate composition.

A star's metallicity offers a window into its past. The universe's pioneering stars, termed Population III, took shape in a metal-scarce universe. Born from the primordial gases, their metallicity was nearly non-existent. However, their demise enriched the cosmos with metals, setting the stage for subsequent generations of metal-rich stars.

Ursa Major II Dwarf (UMa II dSph) is a remarkable dwarf spheroidal galaxy located in the Ursa Major constellation. Dominated by venerable stars, their starkly low metallicity suggests their genesis during the universe's early epochs. These stellar relics serve as silent witnesses to a time when the universe was just embarking on its metal-making odyssey.

The first metal-rich stars could have appeared around 10 billion years ago, give or take a few billion years, as the metallicity of the interstellar medium increased with successive generations of star formation and death. Our solar system and Earth, having formed around 4.5 billion years ago, reside in the Milky Way's Orion Arm. This location is roughly halfway out from the center of the galaxy, a region rich in heavier elements, remnants from the life cycles of previous stars. These heavier elements are believed to have played a crucial role in the emergence of life, providing the essential building blocks for complex molecules and, eventually, life as we know it.

The Beginning of Chemistry

From the simplicity of the earliest elements generated during cosmogenesis to the more varied products of stellar furnaces, the universe amassed a collection of atomic building blocks. The primordial and subsequent stellar nucleosynthesis processes not only populated the cosmos with a diverse array of elements but also set the stage for the intricate dance of atoms that characterizes chemistry. With the dispersion of these elements into the interstellar medium, the foundations were laid for the complex interactions that would give rise to molecules, minerals, and ultimately the varied materials that make up planets, comets, and other celestial bodies. This burgeoning chemical diversity was a critical step toward the development of the rich, compound-laden environments that are fundamental to the emergence of life.

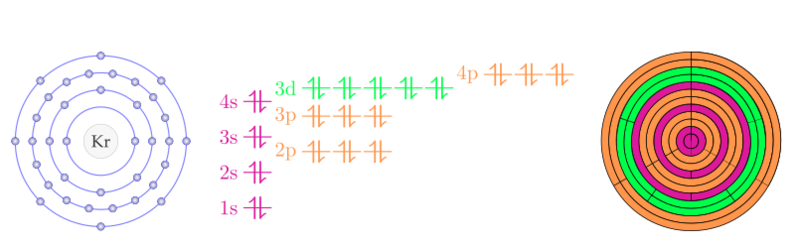

The Bohr model is a recognized method for illustrating atoms, but it lacks the details of the electrons' specific orbitals and their behavior. More accurate atomic models, which are based on three-dimensional orbital diagrams from the Schrödinger equation, provide deeper insight, although they can also be insufficient when it comes to practically illustrating the configuration of valence electrons, which is central to understanding the reactivity of atoms. The circular grid model overcomes these limitations by combining the richness of detail in the electron configuration with an emphasis on the circular symmetry of the atom. This model allows us to either illustrate all the electron orbitals or focus on the valence orbitals that are most crucial for the reactivity of the atom.

The octet rule, which is anchored in circular symmetry, is particularly relevant for the elements in the second and third periods of the periodic system. In the circular grid model, noble gases are represented with completely filled valence shells with full circular symmetry, demonstrating their stability and chemical inactivity. This symmetry is depicted using distinct colors: the s-orbitals in a deep sky blue, the p-orbitals in a vibrant magenta-pink, and the d-orbitals in a warm orange, which helps to differentiate the various orbitals in the electron configurations.

In the microscopic world of atoms, electrons occupy regions known as orbitals, each with a unique shape and capacity for electrons. The simplest, the s orbital, is spherical, embracing a pair of electrons. It's the elemental note in the atomic symphony, akin to the pure and singular tone that forms the base of a musical chord. The p orbitals, more complex, consist of three dumbbell-shaped regions in orthogonal axes. They host up to six electrons, reflecting a harmony of twos. Like the first overtone in a harmonic series, they add depth to the atomic tune, enriching the elemental note with dimension. Ascending in complexity, the d orbitals emerge with a cloverleaf pattern, accommodating ten electrons. They resonate with the qualities of the second overtone, a richer and more intricate layer in the musical analogy, providing a canvas for five distinct pairs of electrons. At a higher level of complexity, the f orbitals, with their intricate shapes, can house fourteen electrons. This is reminiscent of the composite harmonics higher in the series, weaving a tapestry of seven paired electron paths. Each additional layer in this electron structure adds to the atom's ability to bond and interact, much like each new overtone enriches a note's timbre.

Understanding the intricacies of atomic models is more than an academic pursuit; it unlocks the secrets of how elements interact on a cosmic scale, from the birth of stars to the chemistry that fuels life itself. It is within these interactions, governed by the rules of orbital configurations, that the universe's grand choreography of chemistry unfolds.

Atoms and molecules, in their journey through space and interactions, appear to follow a cosmic choreography that aligns with achieving harmony in their electron arrangements. This quest for balance is evident in the completion of their orbital shells, a process that resonates with musical consonance in the grand symphony of the universe. When considering the harmonies in the Second Period of the Periodic Table, Lithium, a lone pioneer, sets the stage with a single electron in its s orbital, akin to a solitary note establishing the fundamental pitch. Beryllium joins the harmony, adding a second electron to the s orbital, strengthening the foundational tone like a harmonious duet.

Boron complicates the melody. It retains the s orbital duet but adds a lone electron in a p orbital, a note that clashes slightly with the s orbital's established tone. Carbon mirrors this dissonance, with another electron joining the p orbital ensemble, yet still yearning for a complete connection with the s orbital's melody. Nitrogen takes a step towards consonance. It pairs its two s orbital electrons with a trio in the p orbitals, achieving a partial alignment with the s orbital's resonance. However, this configuration resembles a single melodic line – pleasant but lacking the richness of a full composition.

Oxygen throws a wrench into the harmony. It adds a jarring fourth electron to the p orbitals, disrupting the nascent consonance. Fluorine, however, stands on the precipice of perfect harmony. It lacks just one electron in its p orbitals to achieve a resonant accord with the fundamental frequency in its s orbital. Neon brings the first act to a triumphant close with a complete octet: two electrons in the s orbital and a full set of six in the p orbitals. This complete ensemble creates a rich, stable, and resonant chord, symbolizing the element's chemical completeness and stability. It's like the final, resounding note that completes the octave in this elemental symphony.

Lithium, beryllium, and boron typically shed electrons to attain the noble gas electron configuration of helium, achieving greater harmony. Although boron does not form salts, it engages in the formation of compounds such as BH3, which results in a six-electron configuration. This arrangement might emulate the electron configuration of helium by pushing all its valence electrons away, though it cannot emulate the electron configuration of a neon-like octet, simply because there are not enough electrons to do so. In contrast, carbon, nitrogen, and fluorine actively strive to complete their electron shells, aiming to mirror the harmonious electron configuration of neon. This fundamental pursuit significantly influences their chemical behavior, driving them to form compounds that emulate the electron configurations of either helium or neon.

Reframing our understanding of atomic behavior from the pursuit of the lowest energy to the pursuit of electronic harmony allows us to envision a universe not as a mere collection of passive participants always striving for the least active state, but as an active ensemble of elements continuously striving for a more harmonious existence. This shift in perspective might extend beyond the realm of the physical, potentially having profound psychological implications. If we consider the universe as seeking a state akin to stillness or 'death,' as suggested by the lowest energy principle, we may subconsciously adopt a nihilistic view that colors our approach to life and its purpose. Conversely, envisioning a universe animated by a quest for harmony invites a more vitalistic interpretation, one where dynamism and interaction are valued.

Molecular Harmonies and Aromaticity

In organic chemistry, the concept of resonance describes the delocalization of electrons across several atoms within a molecule. Molecules with more resonance forms are generally more stable because the charge or any electron density is spread out over several locations rather than being concentrated in one area. This distribution of electrons is like having a choir where the sound is harmoniously spread across multiple voices rather than a single, isolated note that stands out.

A molecule with numerous resonance forms allows for a balancing of charges much like a well-composed piece of music balances tones and rhythms to create a cohesive and pleasing harmony. Charges in resonant structures are not fixed; they are fluid, analogous to the dynamics of musical harmony where the interplay of notes leads to a rich and balanced sound. In this way, molecules with a higher number of resonance structures can be seen as more 'harmonious' because they can stabilize charges in various configurations, leading to lower energy and greater stability—just as a harmonious musical piece is energetically pleasing and balanced to the listener. This stabilization is not just a chemical benefit but also a conceptual harmony, tying together the beauty of molecular architecture with the aesthetic principles found in music and nature.

Aromatic compounds epitomize chemical stability and resonance, akin to a symphony's resounding harmony. This stability arises from the wave-like behavior of delocalized π electrons in accordance with quantum mechanical principles, particularly as outlined in Hückel's molecular orbital theory. Aromatic molecules like benzene conform to Hückel's rule, possessing a closed loop of p orbitals filled with a (4n+2) count of π electrons, which corresponds to an unbroken series of constructive wave interference patterns. These electrons fill bonding molecular orbitals that extend over the entire ring, leading to a lower overall energy state and enhanced stability, much as a chord in harmony enriches a musical composition through the constructive interference of sound waves. Here, n can be considered as integers, reflecting the discrete, quantized nature of electron counts that stabilize aromatic compounds.

In contrast, antiaromatic compounds lack the resonant stability of their aromatic counterparts. With a π electron count of (4n), these molecules find themselves in a precarious state where the molecular orbitals include both bonding and antibonding interactions. The wave functions representing the behavior of the π electrons do not interfere constructively across the entire system, leading to destabilization—a condition mirrored in the discordance of musical notes that fail to constructively combine, resulting in a cacophony of unresolved tension. In these cases, (n) can be considered as non-integers, signifying the atypical electron counts that contribute to the destabilization of antiaromatic compounds.

Therefore, aromaticity signifies a quantum mechanical harmony, a state of low energy where electron wave functions constructively overlap to forge a stable system. Antiaromaticity, on the other hand, represents a dissonance within the electron cloud—a state of increased energy and tension, where the electron wave functions are out of phase, leading to destructive interference and instability. By understanding aromatic and antiaromatic compounds through this lens of wave mechanics and electron delocalization, we can draw parallels with the intuitive realm of music, making complex chemical concepts more accessible and resonant with our everyday experiences.

Life’s Genesis and Early Evolution

The Genesis of Life on Earth

As the universe’s grand choreography of chemistry unfolds across galaxies, seeding planets with the chemical potential for complexity, our gaze turns closer to home—to Earth, a unique stage where the cosmic dance reaches a crescendo in the genesis of life. The conditions on early Earth, a blend of chemical richness and environmental factors, created a crucible for the first biological molecules to form. This moment in history marks not just a milestone for our planet but a turning point in the universe’s story: the emergence of life from non-life, or abiogenesis.

The consolidating force embodies a profound impetus for the amalgamation of smaller systems into larger, more intricate configurations, serving as a universal architect of complexity and connection. This force stands in a dynamic interplay with the principle of entropy, which dictates a natural progression towards dispersion and disorder within systems. Dissipative structures, such as hurricanes, the mesmerizing patterns of a Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction, the organized flow of a river delta, and the complex thermal convection cells that form in a boiling pot of water, emerge as islands of order in the sea of entropy. These structures harness and channel the universe's inherent tendencies towards dispersion to foster the creation of more organized, complex systems. This phenomenon can be seen as a dance between the consolidating force and entropy, where the former guides the latter's drive towards dissipation in such a way that new levels of organization are achieved. It is within this dance that the consolidating force begins to sculpt increasingly complex dissipative structures, weaving together the threads of entropy and order into a tapestry of complexity.

Beneath the ocean's surface, the enigmatic depths near volcanic vents served as nurseries for the earliest forms of life, cradled by the consolidating force—the universe's inherent drive towards complexity and connectivity. These chemical-rich environments offered the ideal stage for simple molecules to begin their transformative odysseys, spurred on by this universal force.

In these undersea forges, long chemical pathways, intricately designed to dissipate energy, embarked on a journey of natural optimization. Initially effective yet rudimentary, these pathways gradually evolved under the dual pressures of environmental challenges and the consolidating force's subtle nudging. Mutations and the harsh realities of the vent environments acted as catalysts for the emergence of new molecular arrangements, streamlining the process of energy dissipation. Configurations that excelled at reducing energy gradients became dominant, marking a pivotal shift towards more refined and efficient mechanisms. This evolutionary trajectory is a reflection of the broader cosmic dynamics, illustrating how systems, from the molecular to the galactic, are intrinsically inclined to optimize their functions and interactions within the environmental constraints they face.

As these chemical systems became increasingly sophisticated, they started to bridge the gap between simple chemical reactions and the complex processes characteristic of primordial biological life. This transition was not merely a series of chemical accidents but a guided evolution, propelled by the consolidating force towards higher states of organization and connectivity. The journey from rudimentary chemical interactions to the dawn of life encapsulates a microcosm of the universe's drive for harmony and complexity, a testament to the continuous influence of the consolidating force in shaping the fabric of existence.

The emergence of life from these primordial conditions underscores the inevitability of complexity and connectivity in the universe. Far from being an anomaly, the rise of biological systems represents the culmination of the universe's relentless push towards creating intricate, interconnected forms of existence. Life on Earth, and potentially elsewhere in the cosmos, stands as a profound example of the consolidating force's capacity to harness the chaotic tendencies of entropy and mold them into structures of astonishing complexity. From the simplest unicellular organisms to the vast networks of neural, social, and ecological systems, life exemplifies the ongoing dance between entropy and order, a dance orchestrated by the consolidating force that weaves the universe into a continuously evolving tapestry of complexity and interconnectedness. This narrative not only deepens our appreciation for the origins of life but also illuminates the underlying unity and purpose that permeate the cosmos, revealing a universe eternally striving for greater harmony and complexity.

Early Metabolic Pathways

The continuous narrative of life's origins unfolds further as we delve into the realm of early metabolic pathways, the intricate networks at the heart of all living organisms. These pathways trace their beginnings to an Earth steeped in a primordial atmosphere rich with methane, ammonia, water, and hydrogen gas. Against a dramatic backdrop of constant volcanic eruptions, intense UV radiation, and the electrical dance of lightning strikes, our planet operated as a colossal chemical crucible. It was in this tumultuous environment that complex organic molecules arose from simpler substances, setting the stage for the biochemistry of life within the proverbial 'primordial soup.'

In an era devoid of photosynthesis and the harnessing of sunlight, early life forms had to ingeniously extract energy from their immediate environments. Chemosynthesis emerged as a remarkable biological workaround, with bacteria and archaea, known as chemolithoautotrophs, harnessing the energy from inorganic substances to synthesize glucose. These organisms thrived in the abyssal darkness of deep-sea hydrothermal vents, using molecules like hydrogen sulfide to convert carbon dioxide into organic matter.

One notable chemosynthetic pathway is methanogenesis, which allowed methanogen archaea to derive energy by producing methane from substrates such as carbon dioxide, acetate, and methyl groups. These methanogens prospered in the anaerobic niches of early Earth, breaking down organic matter and contributing methane to the burgeoning atmosphere.

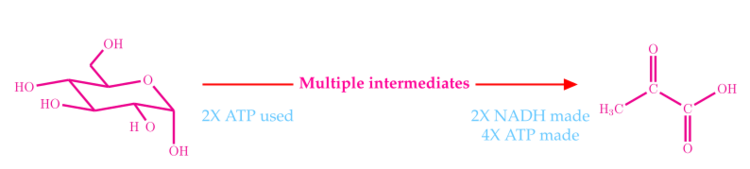

Concurrently, glycolysis, an indispensable anaerobic process, emerged. Through this pathway, bacteria and archaea broke down glucose into pyruvate, producing the vital energy carriers ATP and NADH. The question of glucose's origin in a world lacking photosynthesis suggests that environments like hydrothermal vents may have been the arenas where chemolithoautotrophs manufactured glucose from carbon dioxide and water, using hydrogen sulfide for energy in a process echoing photosynthesis's objectives but powered by chemical reactions rather than sunlight.

These metabolic pathways were more than mere channels for energy; they were the biochemical artisans of life, assembling the essential molecules that form living organisms. They crafted complex molecules, from amino acids to nucleotides, which are the fundamental components of living cells.

Synthesis of DNA Bases

The synthesis of the basic components of DNA, including the purine and pyrimidine bases, may have evolved from simpler chemical reactions that were possible in the absence of enzyme catalysis. Early biopathways likely relied on the availability of small molecules like formaldehyde, cyanide, and ammonia, which are capable of forming larger biomolecules under the right conditions, such as in the presence of mineral surfaces or within hydrothermal vents.

These early reactions could have led to the formation of ribonucleotides, precursors to the modern DNA bases. Ribonucleotides could form spontaneously in a process that mirrors the abiotic conditions believed to be prevalent on the primitive Earth. For instance, the formation of purine bases might have involved the fusion of smaller molecules into a ring structure that later became part of the more complex nucleotides through a series of condensation reactions.

Similarly, the synthesis of pyrimidine bases could have involved simple molecules coming together in a stepwise manner to form the pyrimidine ring, which then attached to a sugar molecule to form nucleotides. These pathways gradually became more efficient with the advent of catalytic RNA molecules, or ribozymes, which could have facilitated and sped up chemical reactions before the evolution of protein enzymes.

As life evolved, these rudimentary pathways became more sophisticated and regulated, involving enzymes that improved the efficiency and specificity of these reactions. This evolutionary process ensured the reliable replication and repair of genetic material, a fundamental requirement for the development of more complex organisms.

The Pentose Phosphate Pathway

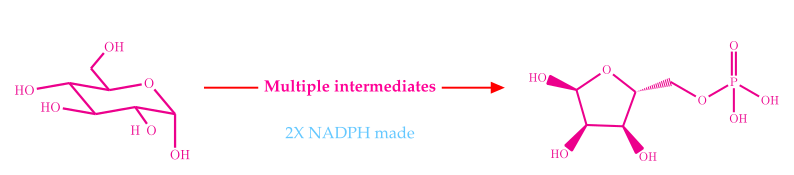

The Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP) is another testament to ancient metabolic ingenuity, generating reducing power in the form of NADPH. It was a bulwark for life before Earth's atmosphere became oxygen-rich, offering both biosynthetic capabilities and protection against oxidative damage. The PPP was also central to the evolution of genetic material due to its production of ribose 5-phosphate, a nucleotide component.

The Shikimate Pathway

The Shikimate Pathway, with its profound evolutionary significance, has been integral for prokaryotic organisms in synthesizing the aromatic amino acids—phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan. These amino acids are the building blocks of proteins and serve as precursors for a plethora of secondary metabolites that are essential for a myriad of cellular functions and ecological interactions. The absence of this pathway in animals reveals a deep dietary dependence that is woven through the fabric of life, linking the simplest of microbes to the most complex animals in a delicate nutritional symbiosis.

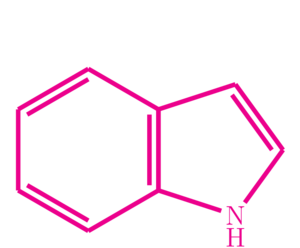

Expanding on the theme of aromaticity in biology, the indole compound emerges as a critical example of nature's utilization of aromatic structures. At its core, indole features a benzene ring fused to a pyrrole ring, a structure that endows it with robust aromaticity essential for its biological roles. One of the paramount indole derivatives is the essential amino acid tryptophan, a cornerstone of protein synthesis and a precursor to serotonin—a neurotransmitter that is fundamental to mood regulation and neuronal function.

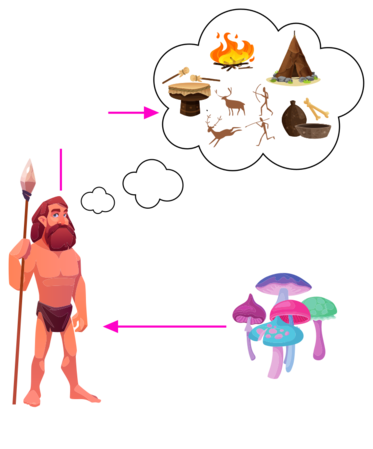

The indole framework is also pivotal in the realm of psychopharmacology, serving as a foundational structure for many psychedelic compounds that target the 5-HT2A receptor, a protein known to influence cognitive processes and perception. These psychedelics, often distinguished by their dramatic impact on consciousness, are unified by the indole ring. This shared structural motif suggests a deeper, harmonious link within life's biochemical network, where the same structural paradigms that scaffold our genetic blueprint also enable the intricate workings of the brain and the profound experiences elicited by psychedelic substances.

In the same way that harmony in music is born from the confluence of varied notes and rhythms to form a cohesive opus, the aromatic indole structure demonstrates how a singular molecular pattern can reverberate through different dimensions of life, supporting functions as varied as the storage of genetic information and the complex phenomena of consciousness and perception. This molecular harmony, embodied by the indole structure, resonates through the biological orchestra, exemplifying the universal symphony of life that plays out at the molecular scale.

Coenzyme A Synthesis

Coenzyme A synthesis from pantothenic acid, which is also known as vitamin B5, is a fundamental process in cell biology. Pantothenic acid, after being absorbed by the body from various food sources, is transported into the cell. Within the cell, it undergoes an enzymatic transformation where it is first converted to pantothenate. This molecule then combines with ATP to form 4'-phosphopantothenate through the action of the enzyme pantothenate kinase.

The process continues as the enzyme phosphopantothenoylcysteine synthetase catalyzes the addition of a cysteine molecule to the 4'-phosphopantothenate, producing 4'-phosphopantothenoylcysteine. Further modification of this molecule, including decarboxylation, leads to the formation of 4'-phosphopantetheine.

Finally, 4'-phosphopantetheine is further processed to produce coenzyme A. This step typically involves the addition of an adenine nucleotide through the action of the enzyme dephospho-CoA kinase. Coenzyme A is essential for various biochemical reactions in the body, particularly those involved in the metabolism of fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. It acts as a carrier of acyl groups, facilitating the transfer of carbon units within the cell, which is crucial for generating energy and synthesizing important biomolecules.

The Mevalonate Pathway

The Mevalonate Pathway, essential for synthesizing isoprenoids crucial for cell membrane structure and signaling, signifies the importance of sterols and isoprenoids in the survival of early life and is present in the last universal common ancestor. In parallel, the Non-mevalonate or MEP Pathway, a vestige from early bacterial lineages found in most bacteria and some plant and algal plastids, emphasizes the ancient and vital role of isoprenoids in both structural integrity and functional processes such as photosynthesis.

Beta-oxidation

Simultaneously, beta-oxidation emerged, a process whereby fatty acid molecules are broken down to generate acetyl-CoA for the citric acid cycle, contributing to ATP production. Its widespread presence across life forms suggests an origin predating the last universal common ancestor, marking it as essential for energy storage and utilization in the earliest life forms. Beta-oxidation's conservation through evolution speaks to its central role in life's energy dynamics, exemplifying the evolutionary creativity spurred by the primordial chemical milieu of early Earth. These pathways not only forged a route to harness energy but also paved the way for the construction of life's complex molecular architecture.

These pathways, forming a complex network, have been instrumental in life's evolutionary journey, demonstrating the adaptability of biological systems in Earth's evolving environment.

Cell Membranes

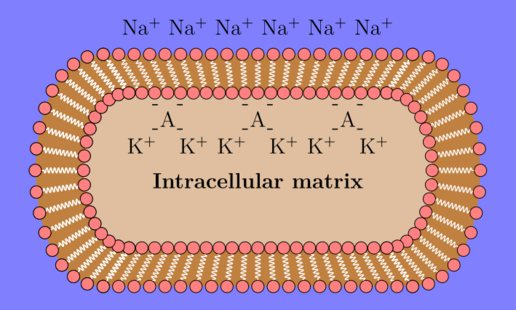

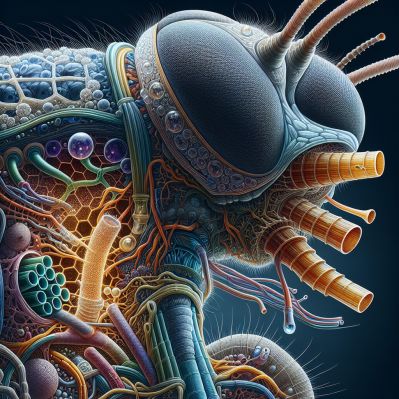

Vital barriers between a cell and its external world are formed by biological cell membranes, chiefly constituted of phospholipids. These phospholipids possess unique characteristics: they have hydrophilic heads that are drawn to water, and hydrophobic tails that resist it, thus forming a safeguarding shell around the cell.

A cell meticulously controls the levels of diverse ions like sodium, chloride, and potassium within its membrane. This intricate regulation, combined with the existence of protein anions that are unable to pass through the membrane due to their size and negative charge, aids in preserving the cell's membrane potential. This represents an electric charge disparity across the membrane. The membrane potential plays an essential role in a variety of cellular activities, including cell communication, signaling, and the movement of substances into and out of the cell.

These contrasting ion concentrations across the cell membrane and the resulting membrane potential are key to keeping cells away from thermodynamic equilibrium. This state of non-equilibrium, or metastability, is essential for life. Cells maintain this metastable state through the metabolism of food into ATP (adenosine triphosphate), the energy currency of the cell. If cells exhaust their food supply, they can no longer produce ATP, which can lead them towards a state of equilibrium, or death.

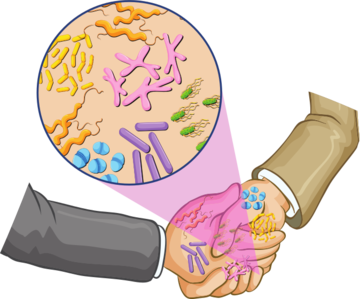

In the vast timeline of life, bacteria and archaea, two distinct sets of organisms, are thought to have diverged from a shared progenitor approximately 3.5 to 4 billion years in the past. This hypothesis is reinforced by genetic and molecular research that reveals unique genetic blueprints and metabolic paths exclusive to these groups, which are absent in other life forms. For instance, certain archaea possess exceptional metabolic systems that enable them to thrive in harsh conditions, including high-salt or high-temperature environments. The evolution of divergent cell membrane structures in bacteria and archaea is conjectured to have potentially contributed to their evolutionary split. Research based on ancient rocks posits that both bacteria and archaea had emerged around 3.5 billion years ago, with some scientists theorizing an even earlier inception.

The Principles of Evolution

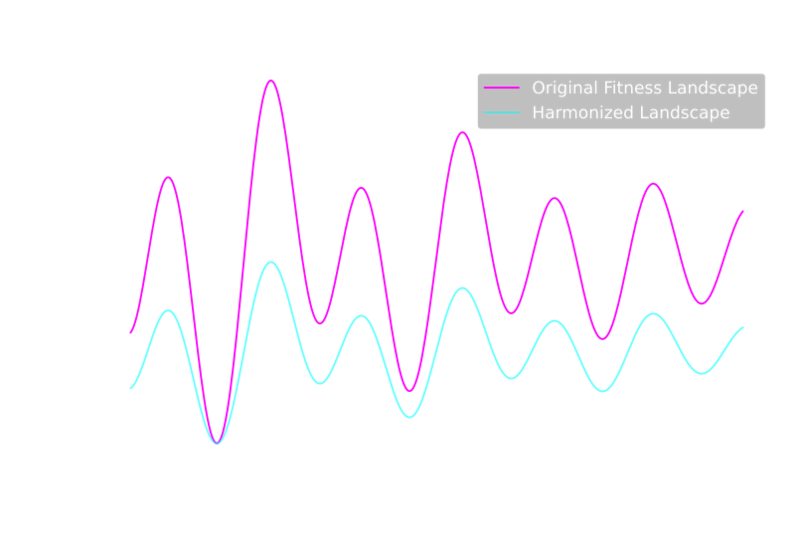

Evolution is not just a historical record of life's past; it is a dynamic framework that explains how organisms adapt and thrive in an ever-changing world. At the heart of this framework is the concept of organisms and niches optimizing for resonance—a powerful metaphor for the ongoing interaction between life forms and their environments. This concept highlights how adaptability and interconnectedness are essential for survival, reflecting the fluidity and responsiveness of biological systems to environmental challenges. As we delve into the principles of evolution, we explore how local optimizations, genetic mechanisms, and ecological dynamics collectively shape the survival strategies of species, influence the balance of ecosystems, and drive the incredible diversity we observe on Earth. This perspective not only enriches our understanding of individual species but also illuminates the broader ecological and evolutionary processes that maintain the ever-changing tapestry of life.

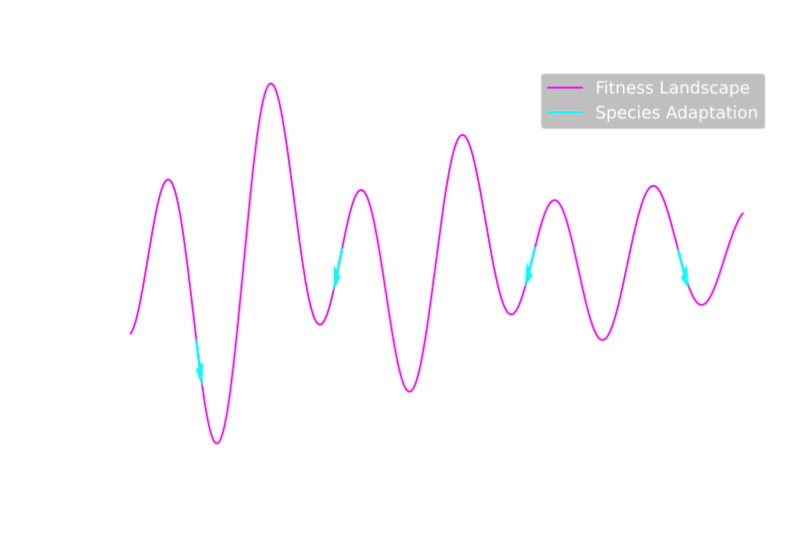

Local Optimization to Get in Resonance with a Niche

Organisms evolve through natural selection to adapt to their specific environmental conditions or niches. This adaptation process can be thought of as a form of local optimization, where each species fine-tunes its physiological, behavioral, and ecological strategies to maximize its survival and reproductive success within its niche. For instance, a cactus optimizes its water retention capabilities to thrive in arid environments, just as aquatic plants optimize their leaf structure for underwater life. The concept of "resonance" in this context is likened to a state of equilibrium or harmony between an organism and its niche. When an organism has effectively optimized its survival strategies to match the specific demands of its environment, it achieves resonance, ensuring that its life processes, reproductive rates, and ecological interactions are all finely tuned to exploit the current conditions maximally.

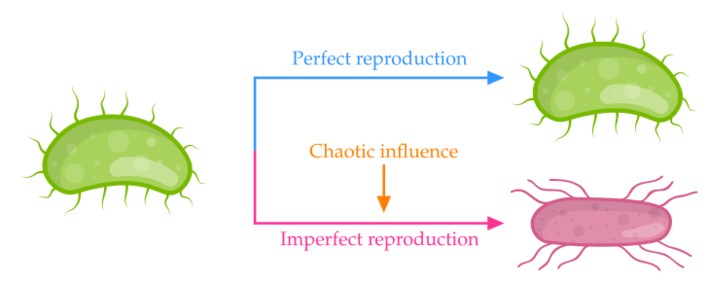

Optimization for a niche relies on imperfect reproduction and variable survivability. Randomness or chaotic elements are integral to this process, contributing to genetic variation within populations. This variation, in turn, provides the raw material for natural selection, enabling the emergence of new traits and, ultimately, driving the incredible biodiversity we observe on Earth. Evolution thrives on a delicate balance of order and chaos. While a modicum of randomness is vital for spurring evolutionary changes, an overabundance can lead to chaos and instability. Without appropriate regulation, excessive genetic diversity could breed harmful mutations, threatening the survival of species. Consequently, life has developed a sophisticated suite of mechanisms designed to mitigate errors in our genetic blueprint.

Delving into the microscopic realm, a key safeguard against inaccuracies is the meticulous proofreading functionality of DNA polymerases. These specialized enzymes duplicate DNA and can correct any missteps made during this process to uphold the integrity of the genetic code. Complementing this, another essential mechanism at the molecular level is DNA repair. Through the concerted efforts of a suite of dedicated enzymes, this process detects and fixes a variety of DNA damages. If this damage goes unrepaired, it could cause discrepancies in the genetic code, resulting in detrimental mutations or, in severe cases, even leading to cancer.

In the grand scheme of evolution, organisms have developed intricate systems beyond the molecular scale to minimize errors and ensure survival. These systems, encompassing feedback loops, regulatory networks, and homeostatic mechanisms, are designed to maintain a stable internal environment and proficiently respond to external changes. Feedback loops and regulatory networks enable organisms to optimize their internal functions in response to alterations in external conditions. On the other hand, homeostatic mechanisms preserve a consistent internal environment, irrespective of external environmental fluctuations. All these mechanisms are integral to the ongoing process of life's evolution on our planet.

In addition to genetic variations, phenotypes can also be profoundly influenced by external environmental factors and inherited through non-genetic means such as epigenetics. Environmental stresses and lifestyle factors can lead to epigenetic changes that modify gene expression without altering the DNA sequence. These changes can be passed from one generation to the next, affecting how organisms respond to their environments and potentially leading to new adaptive strategies. Such mechanisms allow populations to rapidly adjust to new challenges and opportunities, supplementing the slower process of genetic evolution.

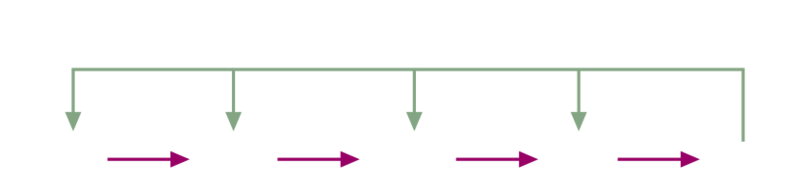

Dynamic Changes and Cross-species Optimization for Collective Resonance

Niches are dynamic, constantly evolving due to factors such as climate change, geological events, the introduction of new species, or shifts in resource availability. These changes can be gradual or abrupt, each posing different challenges and requiring different responses from the organisms involved. When a niche changes, the previously established resonance is disrupted, prompting organisms to adapt anew. This adaptation may involve minor adjustments or, in cases of significant environmental shifts, more radical transformations. For example, some forest-dwelling creatures might start to thrive in urban settings if their natural habitats are destroyed, optimizing for this new urban niche. Similarly, aquatic species may adapt their behaviors and physiological processes in response to increased water temperatures or decreased salinity, showcasing the broad spectrum of adaptability across different ecosystems.

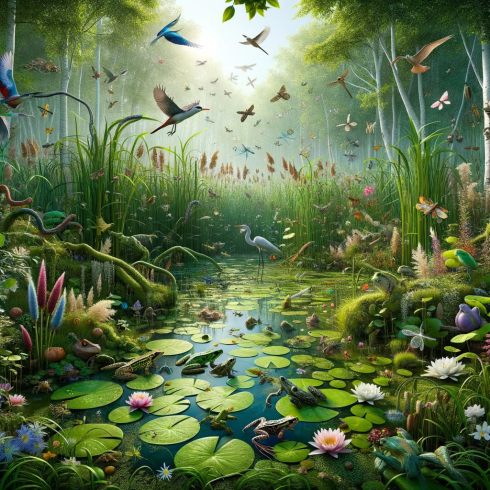

On a broader scale, ecosystems function as intricate networks of interlinked niches, each populated by species uniquely adapted to both their immediate environments and the activities of their ecological neighbors. Such interdependence among species means that the behavior of one can significantly influence the conditions within adjacent niches, fostering a dynamic equilibrium throughout the ecosystem. This interconnectedness necessitates a certain level of synchronization among various biological rhythms, including food consumption and reproductive cycles, across different species. Harmonizing these rhythms is crucial, not just within individual species but across the entire community, to maintain the ecosystem's overall stability and resilience. Over time, these interactions often lead to a state of collective resonance, where the life cycles and behavioral patterns across species become more aligned, enhancing the sustainability of the ecosystem.

In any given ecosystem, the availability of resources dictates the feeding patterns of species. These patterns must be synchronized with the resource regeneration rates and the consumption needs of other species within the same ecosystem. Predators must balance their consumption rates with the breeding rates of their prey to avoid overexploitation. If a predator's feeding pattern is too aggressive, it may deplete the prey population, leading to starvation and a potential collapse in the predator population as well. Different species competing for the same resources must adapt their consumption patterns to survive alongside each other. This could involve temporal partitioning (different times for resource use) or spatial partitioning (using different areas for resources), which are forms of ecological harmonization.

Breeding patterns also need to be in sync with ecological cycles and the life cycles of other species. Many species time their reproductive events to coincide with periods of high food availability. This synchronization ensures that offspring have the best chance of survival. For instance, many bird species time the hatching of their chicks to coincide with peak insect availability in spring. In some cases, the reproductive success of one species can directly impact the survival of another. For example, the breeding season of certain insects might need to align with the flowering period of specific plants for pollination to occur effectively.

To illustrate further, consider the role of keystone species, such as bees in pollination. The optimization of bees for their niches not only supports their survival but also enhances the reproductive success of the plant species they pollinate, demonstrating a mutualistic relationship that stabilizes various other niches within the ecosystem. The interplay of these dynamic changes and cross-species optimizations contributes to the resilience and stability of ecosystems. Understanding these interactions helps us appreciate the complexity of natural environments and underscores the importance of preserving biodiversity to maintain ecological balance. This holistic view is essential for effective conservation strategies and for predicting how ecosystems might respond to future environmental changes.

The concept of resonance in ecology can be likened to a well-orchestrated symphony where each participant (species) plays its part at the right time and with the right intensity. Such orchestration leads to what might be considered a form of collective resonance. In ecosystems, this involves positive and negative feedback mechanisms among different trophic levels that help to regulate and stabilize ecosystem functions. These interactions and interdependencies among species contribute to a dynamic equilibrium, where changes in one part of the ecosystem necessitate adjustments in others, thus maintaining overall system health and functionality.

Understanding these intricate interactions is crucial for appreciating the complexity of natural environments and underscores the importance of preserving biodiversity to maintain ecological balance. This holistic view is essential for effective conservation strategies and for predicting how ecosystems might respond to future environmental changes.

Plate Tectonics

The initiation of plate tectonics around 3 to 3.5 billion years ago marked a pivotal chapter in Earth's geological history. This period saw the transformation of Earth from a relatively static state to a dynamic planet, characterized by the continuous movement of its lithospheric plates.

In the early stages of Earth's history, as the planet cooled, its surface began to solidify, forming a crust. This crust eventually fractured under the strains of the Earth's internal heat and movements, giving birth to the tectonic plates. The movement of these plates has been instrumental in shaping the Earth's surface as we know it today. Continents formed, shifted, and collided, leading to the creation of mountain ranges, ocean basins, and the diverse topographical features that mark the planet.

The impacts of plate tectonics extended beyond mere physical transformations. This process influenced the Earth's climate and the evolution of life. The shifting of continents affected oceanic and atmospheric circulation patterns, contributing to changes in climate over millions of years. Mountain building and volcanic activity associated with plate movements played significant roles in atmospheric evolution, impacting the development and distribution of life forms.

Moreover, plate tectonics has been central to the long-term carbon cycle, crucial for maintaining Earth's habitability. By cycling carbon between the Earth's surface and interior, it helped regulate atmospheric CO2 levels, thus playing a key role in the Earth's climate system.

The onset of plate tectonics was thus more than a geological event; it was a transformative process that shaped not only the physical landscape of the planet but also its environmental conditions and the life it supports. This dynamic process set the stage for the continually changing and evolving planet, influencing everything from climate patterns to the evolution of species.

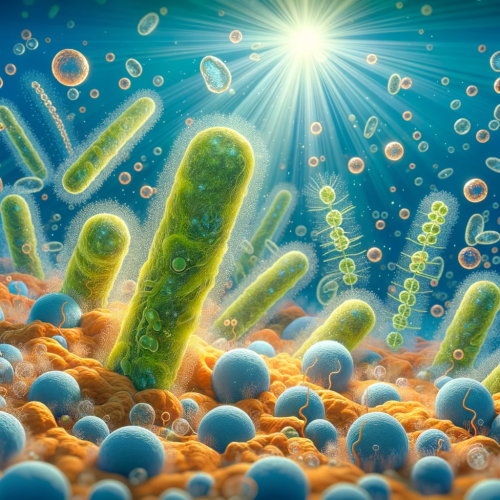

Cyanobacteria and the Great Oxidation Event

One notable member of the bacterial realm, cyanobacteria, was instrumental in molding the early Earth's environment. Capable of performing photosynthesis, these organisms harnessed sunlight to transform carbon dioxide and water into energy, liberating oxygen as a side product. Cyanobacteria also hold the unique capability to convert atmospheric nitrogen into a form that can be utilized by other life forms.

Approximately 2.4 billion years in the past, a momentous incident known as the Great Oxidation Event unfolded. This was characterized by a sudden and dramatic surge in the levels of oxygen in Earth's atmosphere. This noteworthy episode signified a crucial turning point in the annals of Earth's history, instigating a series of profound alterations in both the atmosphere's constitution and the surface of the planet. The prevailing theory posits that the rapid multiplication of cyanobacteria sparked this event. The photosynthetic processes of these bacteria resulted in an enormous release of oxygen into the atmosphere.

In a transformative process, cyanobacteria began to produce oxygen, which then reacted with various gases such as methane. This interaction led to the formation of a variety of more complex molecules, including ozone. Likely, it also facilitated the oxidation of methane into CO2, effectively lessening the greenhouse effect and triggering a period of global cooling.